Moving Experiences Matter:

Changing the Worldviews of Chicago students via a Study Abroad Project to Cape Town, South Africa

By Ken Salo, Urban and Regional Planning

In Fall 2011, I once again led about twenty UIUC students from mainly suburban Chicago, IL in debates with their counterparts from the townships of Cape Town about how they differently experience, imagine and work to transform their segregated cities. As a South African who spent many of my younger years growing up in Cape Town, leading a study abroad tour of mainly white middle class North American youth to my cultural backyard can be both physically and intellectually trying. But ultimately it is also rewarding. Every year while undertaking the course and experiencing the headache of trying to rein in my students as they wander the streets of Cape Town, I promise to be kinder to myself and not to do it again.Then by the end of the trip, upon return and observation of my students’ transformative experiences, I sign up for teaching the course yet again as soon as the call for applications goes out. So this winter break 2012-2013, I am signed up yet again to offer the course in South Africa to a group of UIUC undergraduates. So what motivates me to annually move students from their local homes and comfort zones to my backyard abroad?

As competitors for a seat in my GLBL 298 study abroad course, some, mainly black female students, declare that they want to reconnect with “Africa: their Motherland”; other, mainly white males, desire to explore an “exotic off-the-chart place” (where the wild things are); yet others, mainly white females, want to “teach and empower urban Africa’s downtrodden masses”; and lastly, some study abroad veterans, “want to experience their last life-changing adventure before graduating.” A few socially conscious students are indeed motivated to explore and compare how Cape Town’s still segregated spaces shape its persistent social inequalities of race, class, gender and generation and to compare these processes with those fragmenting Chicago.

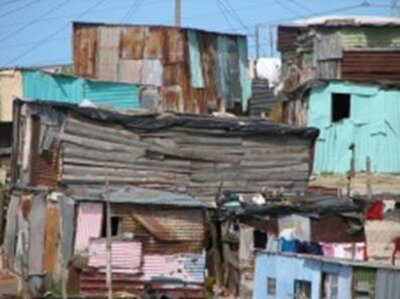

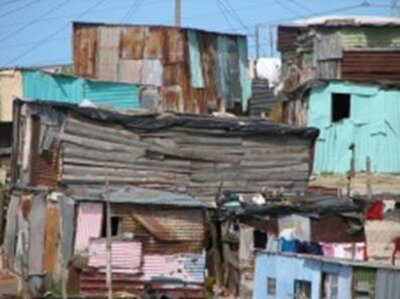

The course is structured in two parts: a pre-departure series of six weekly meetings where we predominantly read state and academic histories of Cape Town’s transformation followed by a two week field trip to explore local stories of urban transformation via resident-led walking tours. Usually half way into our course, students agree with the me that critical urban theorists, David Harvey and Dolores Hayden, can help us understand how capitalist cities change and especially how stigmatized urban danger zones can be transformed into spaces of hope for a more just and humane city. In brief, they argue that any attempt to construct a just and humane future city should be built with, not upon, the ruins of past struggles against urban injustices and starts with recovering the multiple and still largely invisible and insurgent stories of marginalized urban outcasts. More importantly, we agree that our main academic mission is to compare how the lived experiences and stories of the urban poor subvert state claims of urban transformation. To realize our mission, students write a pre-departure essay about their expectations. These reflective pre-departure essays are based on assigned readings and documentaries observed on campus, studying state histories explaining how contemporary Cape Town has both transformed and continued its colonial and apartheid past. The first two weeks in Cape Town students engage in resident-led field trips and walking tours of iconic sites of anti-colonial, anti-apartheid and anti-neoliberal struggles. These include the Downtown Slave Lodge, District Six Museum, Robben Island, Community House, Lwandle Museum of Migrant Labor and the Blikkiesdorp Temporary Resettlement Area. Following these field trips and resident-led debates, students submit a journal of their experiences. In these post-departure or post-field- visit journals they reflect on how their experiences and expectations differ; how what they have learned through observations and conversation with residents confirms or challenges their prior assumptions; and how these have changed the ways they look at their own experiences and life spaces, e.g. in Chicago.

Without going into details, each time I review returning student journals, I am once again inspired by the ability of experiential learning opportunities such as study abroad projects to expand student worldviews and their vocabulary to express this transformation. Reading their journals reminds me of Brazilian educator Paolo Freire’s insistence for a pedagogy grounded in the experiences of poor, oppressed people struggling to transform their world if we desire to transform the worldviews of our privileged students. Their stories of the mismatch between their expectations and experiences testify to the limits of formal, academic ways of knowing and the need to pursue other experiential ways of learning to correct our academic blind spots.

Several returning students sometimes write to assure me that Cape Town is no longer an exotic, wild destination in a nostalgic Motherland. They write about their life-changing experience and how the course has helped them see Cape Town, like their native but now de-familiarized Chicago, as a privileged site of struggle by poor people of color against the global urbanization processes that continue to exclude them from the cities they produced. In response, I thank them in return for their inspiring words and usually remind them of Chinua Achebe’s insight in Arrow of God (1968) that “the world is like a Mask Dancing, to see it well, you don’t stand in one place.” I think that’s what has moved me to take twenty students every winter break from Chicago to Cape Town for the last seven years.