Beth Ann Williams, Doctoral student in History and CAS FLAS student

Kenya and Tanzania Travels

Seven weeks and five different locations. My summer 2015 travels, Predissertation research funded by the History Department, took me throughout East Africa as I searched for archives and met with local leaders to lay the groundwork for future oral interviews. While not my first trip to the region, summer 2015 was my first journey as a lone scholar, not a student living with other Americans or a teenager traveling with her family. The trip took me through a range of environments, places both rural and urban, and introduced me to a host of new connections.

I started in Nairobi, Kenya. The big city felt like a maze of challenges for this small town girl. One week into my stay I bought a new dress and jacket so I wouldn’t feel out of place among the many businesspeople powerwalking around downtown. I also got my hands very dirty (literally) paging through the archives of the Kenya National Archives and Anglican Church of Kenya. Most of my favorite memories, however, are completely unprofessional: sitting in Uhuru (Freedom) park next to the empty carnival, attending TED-like dinner events with other young professionals, and eating delicious Ethiopian food at Habesha.

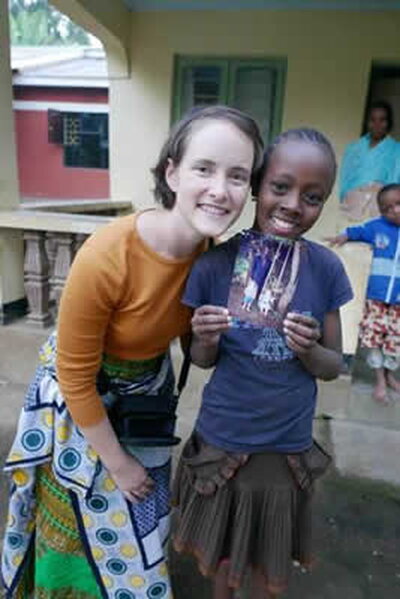

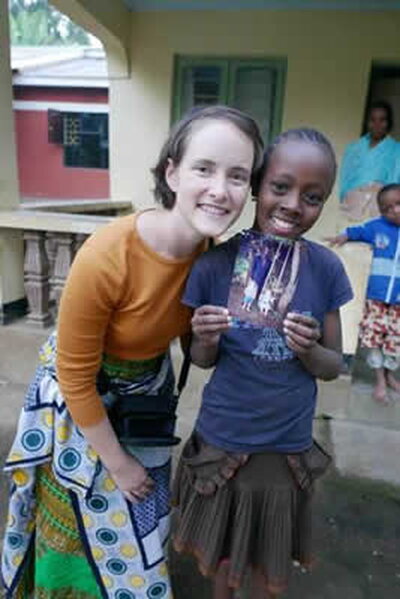

From Kenya I moved south to neighboring Tanzania. In the middle of the cool season, the northern towns of Arusha and Moshi were green and full of Western tourists and volunteers. In Makumira, a rural area close to Arusha, I spent five delightful days with old family friends. I loved being able to surprise my namesake, Anna, with my improved Swahili conversation ability. She, in turn, startled me by bringing out old family pictures of my family in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

In Moshi, I stayed at a nonprofit where young women are trained for hotel and hospitality work in the tourism industry. It was a little overwhelming but so much fun to return home each night after trying to move forward with research to receive greetings from 30 new acquaintances. I ate dinner with them almost every night and felt like I was not alone in the region. I was sad to leave Moshi, but after a short five days I moved south yet again to my final destination, the Tanzanian capital of Dar es Salaam. Dar is much hotter than Moshi, even in the cool season. They make up for the heat with beautiful beaches, a luxury most residents never get to experience. Instead Dar’s inhabitants fight the traffic to seek opportunities and jobs in international business and government that are only accessible in the big city.

Looking back over my whirlwind trip, I feel wonder at the variety of geographies, climates, and relationships that filled my summer. From urban concrete mazes to quiet dinners under the shadow of Mount Kilimanjaro to hot afternoons near the ocean East Africa keeps you on your toes. I cannot wait to get back!

Ken Kittrell, B.S., Kinesiology, 2012

“I-Believe” In South Africa

Often people will incorporate birthdates, addresses, or even personal identification numbers to distinguish their passwords; I use the date I left home to study abroad in South Africa. Getting the opportunity to studying abroad is an important period of any student’s life. There are many elements of the experience that make it easy to become elated once the notion to venture around the world sets in one’s mind. The chance to explore a new culture, discover new methods of research, visit a new part of the world, meet new people—all while learning more about a specific topic through total immersion in the field—had all the allure that made studying aboard a necessary part of my collegiate experience. I had always been interested in one day visiting Africa and found an opportunity through a class listed as Global Studies 298 under the guidance of the esteemed and wonderful Professor Ken Salo. The course allows students to research the socio-political and economic landscape of South Africa and an examination into the ways history’s achievements and failures leave lasting impacts on communities, towns, cities, and countries. The opportunity to study abroad broadened the lens through which literature is met with immersion and knowledge from lectures is put into practice. Choosing to study Globalization and Urban Inequalities in Cape Town, South Africa, proved to be a humbling experience filled with vivid, impassioned, and glaring truths that became all the more tangible in the investigation of the lingering effects of this beautiful, post-apartheid country via urban landscapes.

South Africa has continuously stood in contrast to most of its Sub-Saharan Africa counterparts, specifically the number of individuals who reside in urban areas, which is 61% as of 2014 (World Bank, 2014). The sheer level of urbanization within South Africa is a component of its colonial history that was vastly different from its neighbors. Climate similarity with England and other portions of Europe played a large part of why Dutch and British colonialism occurred and led to both countries expanding permanent populations throughout the region. The large transplant of Europeans to the region, as well as the discovery of diamonds and gold, led to a heavily segregated society that was reinforced by capitalistic interests and official government policy. South Africa now exists in a post-apartheid state, but is still addressing issues of stratification and segregation that have been reinforced in urban areas.

During our explorations we visited the spectacular University of Cape Town (UCT) and its Upper Campus, which stands beautifully in the foreground of one of South Africa’s spectacular mountains—Devil’s Peak. Because we came from a university in the Midwest, we met the striking visuals of the campus with awe, admiration, and bit of envy. Overlooking the rugby fields was the bronze statue of Cecil John Rhodes which we learned was erected in honor of his generous gift of the area of land the campus was founded on. However, it would be later learned that Rhodes’s gift was not innocent, but in fact drenched in the blood of the colonized native peoples.

Prior to Rhodes’s arrival, native peoples of South Africa had suffered more than two centuries of Dutch colonization. However it was under Rhodes that British imperialism, through brutal force, consolidated the systematic theft of land. In doing so, Rhodes-lead British imperialism created an army of cheap, landless laborers for extracting South Africa’s mineral wealth, leaving behind an enduring legacy of oppression still impacting citizens today. Reinforced by missionary work in the region, as well as having support from the British crown, Rhodes’s modernization of South African labor removed farmers from the land, as well as land from the farmers, and thus transferred native South Africans to work in the diamond mines. Recently, the Rhodes monument had been the target of hostility due to Rhodes being seen as one of the key components of racial tension and segregation in South Africa. What began as vandalism of the statue and student activism protesting the system that Rhodes imposed, have led to the removal of the statue completely from the UCT campus. The statue was regarded as representing a divisive political figure. The students are fighting for free channeling of political views by the black South Africans for institutions and administrative positions. Students of the university claimed to view the statue as a symbol of institutional racism and representative of not only UCT’s, but South Africa’s, failures in racial transformation, systemic undermining of black voices, and persistence of racial subordination. Apartheid may have ended in 1994 through free elections, but systematic forms of oppression are still present. During apartheid, white supremacy was direct but today it is still in existence through increasing unemployment, poverty, and dehumanizing conditions for black Africans throughout South Africa. Our experience studying abroad shone a necessary light on these issues and gave us an opportunity to work with community activists to generate innovative solutions to a few marginalized communities.

Near the culmination of our trip, Professor Ken Salo arranged for us to meet with local community leaders who were involved in fighting for citizens’ well-being who had been relocated from their homes to temporary housing townships. Listening to community members detail their grievances, explain their circumstances, and call for action by local government enabled our group to gain a far more tangible understanding of everything our books and lectures had thus far taught. As we worked with those community leaders to create action plans to tackle an issue of importance for the citizens of the townships, it became imperative that the work we did would leave a lasting impact that would be sustainable far long after we departed. One component of our final project was a banner that read, “I-Believe.” On this banner we encouraged the children of the Blikkiesdorp Township to write down their career and academic goals. As each child dipped their hand in paint and placed their prints adjacent to what they wrote, we told them this mark would serve not only as a signature, but also as a promise to do everything in their abilities to reach those goals no matter how distant they seemed. To this day, that banner is still raised in the local school in Blikkiesdorp.

Being able to immerse myself in another culture has inspired nearly every action I have taken since our departure and there aren’t enough thank you hugs in the world I can give for the opportunity I had to do so. Cape Town, South Africa, left an indelible mark on me and I will forever remember the passion, struggle, charisma, humor, and warmth that exist strong and proud in its people. Of all my collegiate decisions, studying abroad has still left the greatest impact.